This is a companion blog post to my podcast episode celebrating World Bicycle Day (search Panicky Pictures in your podcatcher). It transcribes the episode, and includes supplementary links, videos and images.

I’m panickyintheuk and this is Panicky Pictures [Wilhelm scream].

I hope June is treating you well so far. I am of course working on a Pride episode, but I thought I’d put out a quick one in honour of World Bicycle Day, the 3rd of June.

So, what comes to mind for you when you think of cycling in films? Maybe Bicycle Thieves or The Flying Scotsman, which totally makes sense, but there’s a film that comes to mind for me which tends to get left off most lists of bike-related movies. I’ll give you a hint:

That’s right! The Kansas analogue of the Wicked Witch of the West, Miss Gulch, rides a bicycle. This isn’t just incidental: during the tornado transformation sequence, her bike turns into a broomstick—the broomstick that’s going to become the MacGuffin for the entire film. Dorothy taking away the Wicked Witch’s broom forms the basis of her hero’s journey—in order to triumph, she has to take away another woman’s mode of transportation. Think about it for a second—it’s not like the broom is a weapon. She’s tasked with curtailing the Witch’s mobility. Meanwhile, the good witch Glinda gets around in a wildly impractical bubble, and Dorothy has to traverse the whole of Oz on foot, wearing heels she can’t take off! They call them slippers, but those are not slippers, those are heels. Imagine how much more quickly she could have got to the Emerald City if she’d had a bike.

I love The Wizard of Oz as much as the next queer (and some people do go both ways), but I think it’s worth noting that here bicycling is associated with being a scary old spinster, and one who is possibly lesbian-coded. Tell me if you think that’s too much of a stretch.

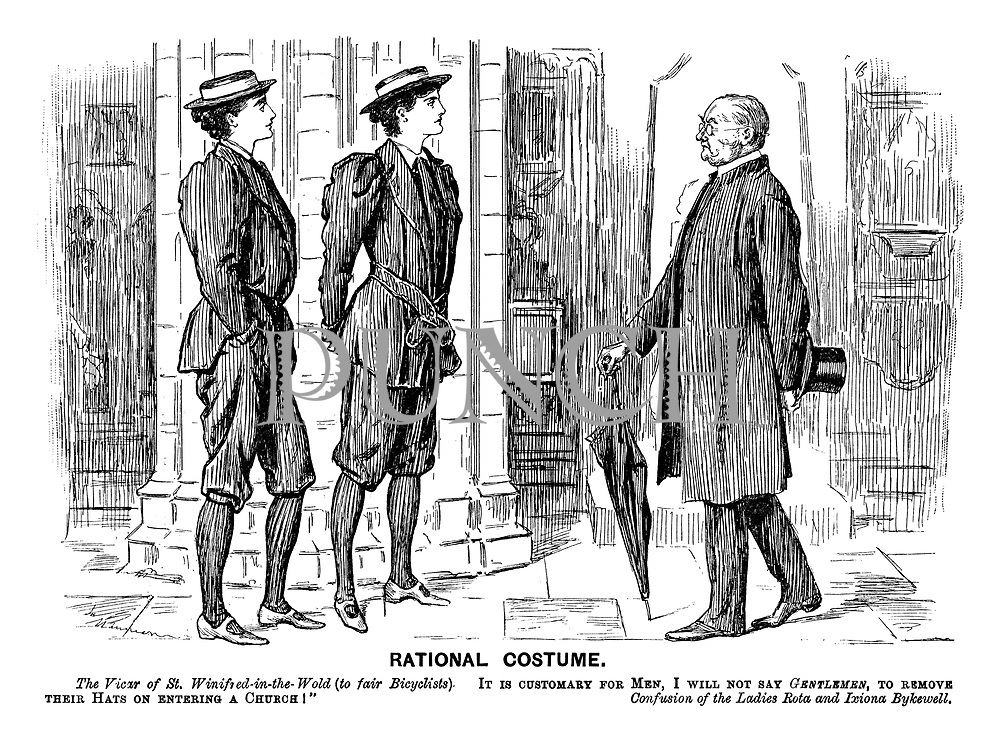

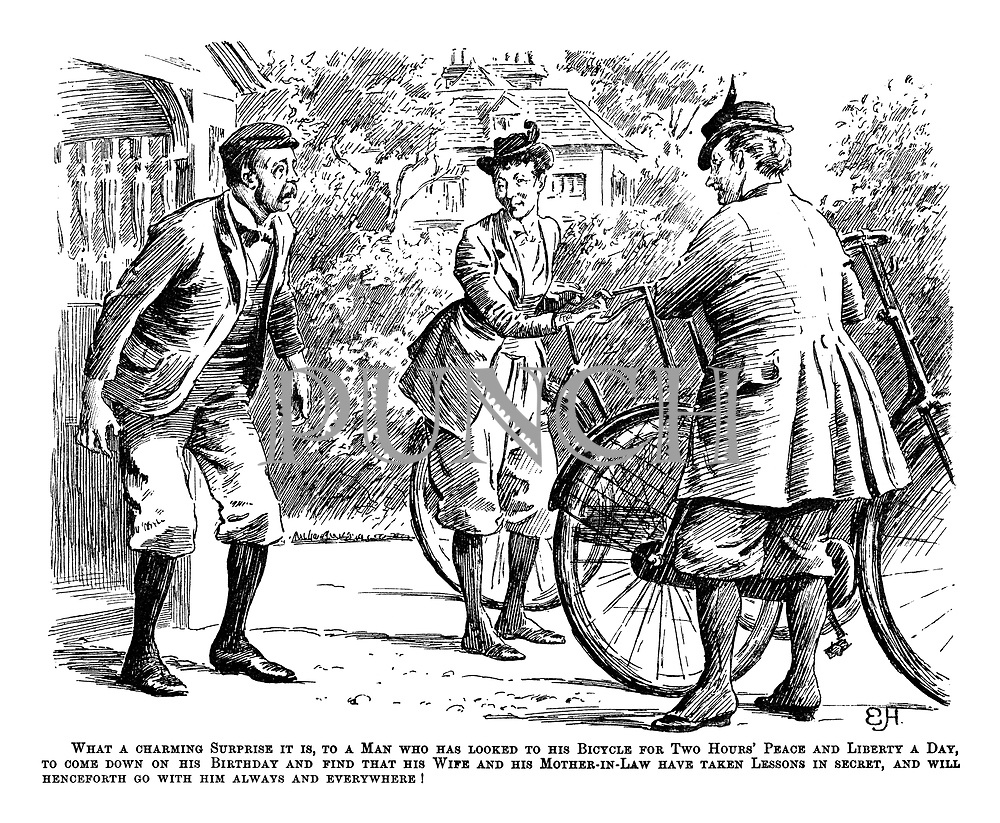

This association wasn’t invented by Victor Fleming. Bikes were a symbol of women’s liberation right from the beginning, provoking a major backlash in the dominant culture. When the safety bicycle—a term used to refer to any bicycle that wasn’t the precarious penny-farthing—became widely available in the late 1880s, cycling was suddenly accessible to women for the first time. This led to a bicycle craze in the 1890s, and also to dress reform, since the restrictive clothing fashionable among women during that period wasn’t conducive to cycling. The more forgiving bicycle suit was invented, and lampooned in several Punch cartoons.

Victorian doctors warned of the dangers of “bicycle face”: a weary, pinched expression, with dark shadows under the eyes. Hey, I look like that whether I cycle or not. These physicians were also much concerned with the masturbatory potential of the bicycle seat.

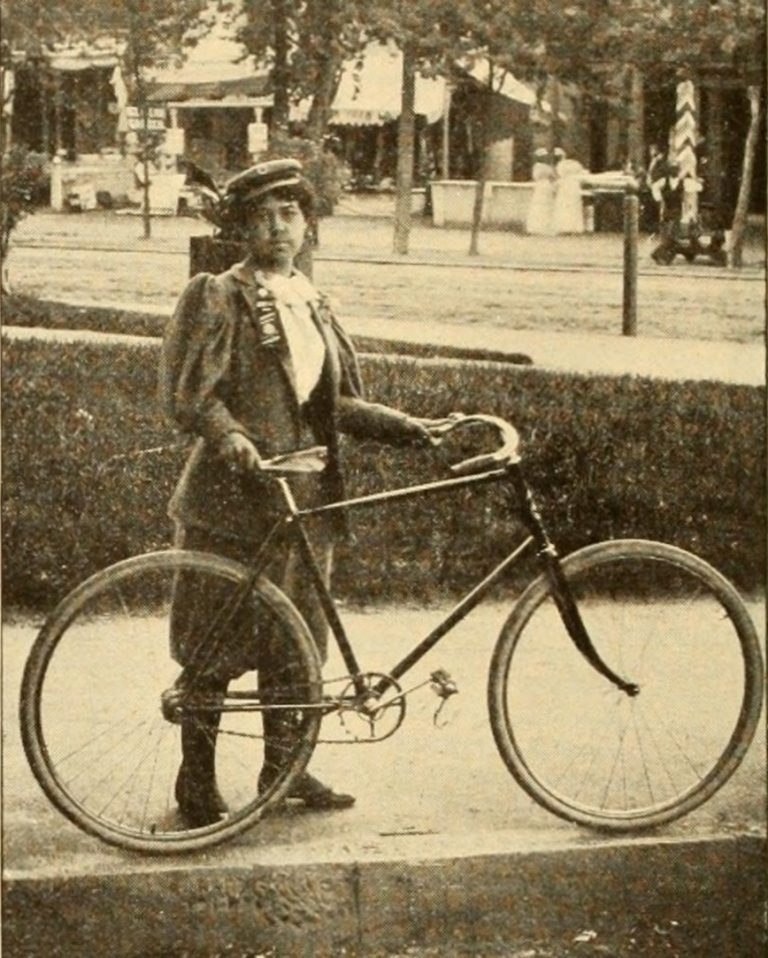

All in all, lady cyclists were characterised as being unattractive, mannish, and frighteningly liberated. Somehow, this didn’t put women off. In 1893, Kittie Knox became the first African-American to be accepted into the League of American Wheelmen. The Jewish-American Annie Londonderry became the first woman to cycle around the world in 1895. In 1896, Susan B Anthony said “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel.”

This might all seem like a relic of the past, but in parts of West and South Asia, there are still limitations on women’s ability to cycle. In Iran, there has been a fatwa against women cycling in public since 2016, and in Saudi Arabia, women can only cycle for recreational purposes, not for transport. In Pakistan there have been regular bicycle rallies since 2018 protesting restrictions against women’s cycling.

The 2012 Saudi Arabian film Wadjda focuses on the rebellious girl of the title, whose one desire is to get a bike like her friend Abdullah. Meanwhile, her mother is dealing with a difficult commute—she can’t drive herself to work, so she’s reliant on an abusive and controlling driver. The film shows us how Wadjda and her mother’s freedom of movement is curtailed by the patriarchal society they live in. A similar dynamic plays out in the 2015 Turkish film Mustang, and to a degree in the 2018 American film Skate Kitchen, though those aren’t about bikes so we won’t linger.

In the West, though, I don’t think a strong link persists between cycling and women’s liberation in mainstream discourse. To the extent that biking is still gendered at all, I think it’s now probably associated more with men. Certainly my perception of pro-cycling is that it seems to be male dominated, and anecdotally, most of the keenest cyclists I know are men, and so are most of the bike mechanics I’ve encountered. But there are other tropes that have sprung up around cycling, particularly in American media.

Whereas cycling was once associated with making women more masculine, now it can be used as a symbol of emasculation or infantilisation for men. In an article for Slate, Nitish Pahwa makes the argument that in American media in particular, bikes are portrayed as dorky. He recently guested on the podcast The War on Cars to discuss this, and in his article he points the finger at American car culture, which became particularly pervasive in the second half of the twentieth century.

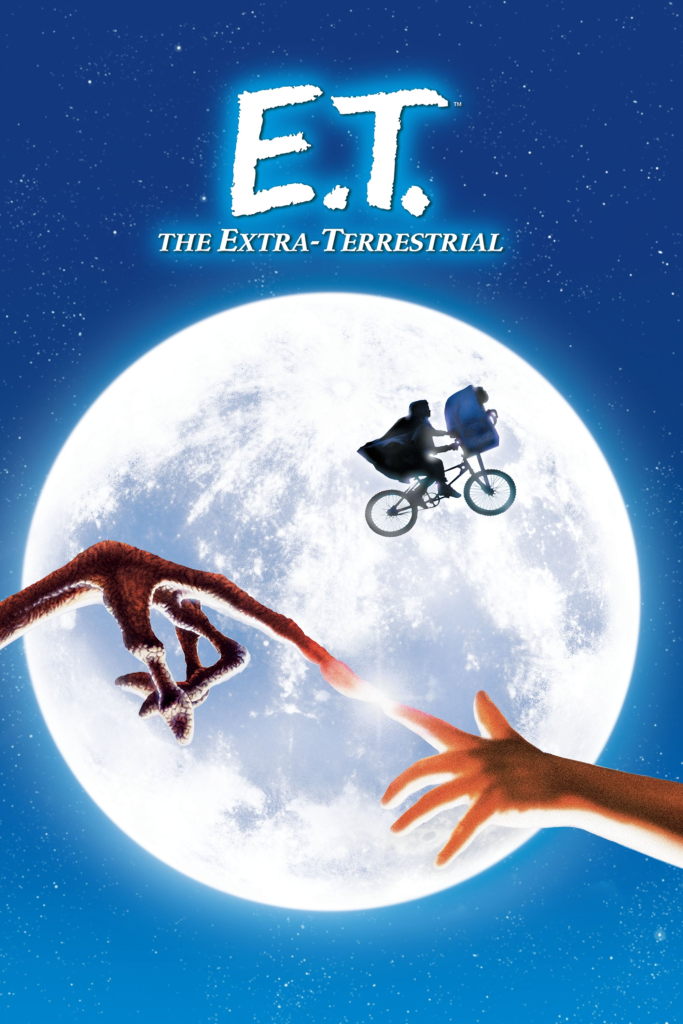

I think there’s a lot of merit in this argument: even when bikes are portrayed positively in American media, they’re often associated with childhood.

Look at E.T.—the bicycle silhouetted against a giant moon on the poster is an iconic image. E.T. was obviously a huge influence on Stranger Things, which has also prominently featured bikes in its promotional materials. Bikes have become so associated with this kind of 80s-set children’s adventure that a TTRPG based on the genre is called ‘Kids on Bikes’.

In these kinds of stories, bikes symbolise freedom and adventure, as well as perhaps a nostalgia for a supposedly more innocent time, when kids could just hop on their bikes and explore without constant parental surveillance. But those associations don’t persist for adult characters, even though I can tell you from personal experience that riding a bike—if you’re lucky enough to live somewhere with a decent cycle network—is incredibly freeing. It feels like flying. And the association between cycling and flight is present in an awful lot of these stories: we’ve already mentioned the bike-turned-broom in The Wizard of Oz and the flying bike in E.T., but what about Tombo’s bike in Kiki’s Delivery Service, which he repurposes into a flying machine? Okay, he ends up getting caught up in a huge gust of wind—Miss Gulch-style—and having to be rescued by Kiki on HER broom, but he’s got the spirit. By the way, the association between bikes and brooms doesn’t end there: a companion game to ‘Kids on Bikes’ is called—you guessed it—‘Kids on Brooms’. Even when cycling is being made fun of, there still seems to be a general acknowledgement that it’s a little bit magic.

Fortunately, car culture isn’t as dominant in most of the rest of the world as it is in the US, and even there, cycling is enjoying a resurgence in some urban centres. The rise of public bicycle sharing systems and the electric bike are making cycling more accessible than ever before to disabled people and those who don’t have storage space. While there’s still an affordability issue, bikes are considerably cheaper to buy and run than a car. Still, I think we have a way to go in recognising the utopian possibilities of the bicycle in mainstream culture. In queer and feminist circles, it’s much more apparent. For example, take a look at the bike-related anthologies edited by Elly Blue, or Gears for Queers by Abigail Melton and Lilith Cooper. Bicycle repair cafés proliferate in anarchist and DIY spaces.

While there are options for disabled cyclists, I do appreciate that cycling isn’t a possibility for everyone. Still, I think that a future in which we, as a society, are much less reliant on cars would be a safer and better world. Cycling is solarpunk, and the sooner Hollywood catches up, the better.

Let’s end with a personal hero of mine. David Byrne recently attended the Met Gala with his bike in tow, and has been an advocate for cycling for years. He might have driven around Texas in 1986’s True Stories, but more recent outings like Ride, Rise, Roar and American Utopia have shown him on his bike. Maybe, together, we can built a future that’s a little less ‘Glass, Concrete & Stone’ and little more ‘Flowers’.